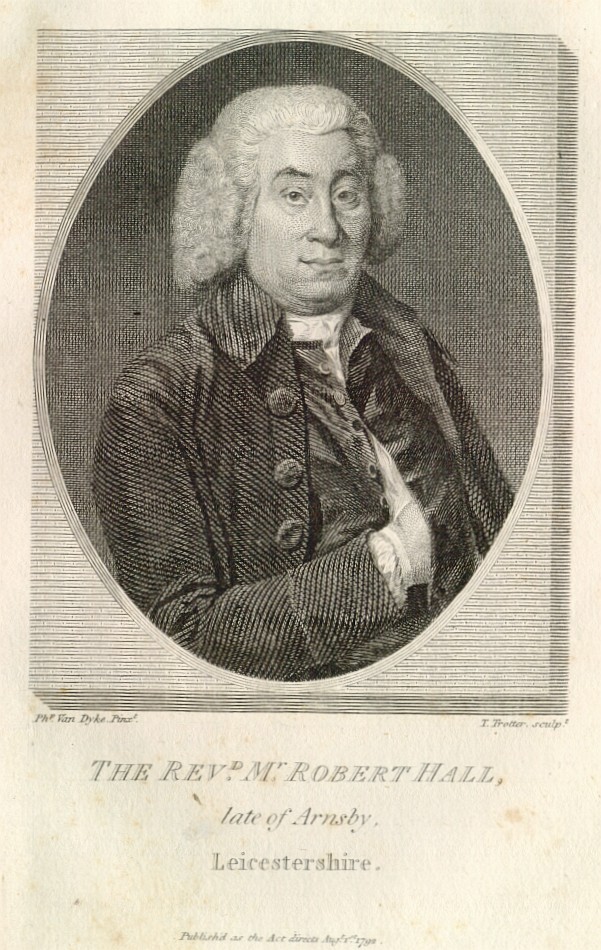

Who was Robert Hall?(2)

Name: Robert Hall

Dates: 1764-1831

THE REV. ROBERT HALL - AN ELOQUENT PREACHER

From Highways and Byways of Leicestershire by J B Firth, Macmillan, 1926

Three miles to the south-west of Wistow is Arnesby, where interest centres in the humble dwelling-house which, in the middle of the eighteenth century, was the home of the Rev. Robert Hall, a Baptist minister, who preached at the little chapel hard by. Here, in 1764, his fourteenth and youngest child was born, to whom he gave his own Christian name. Of the father, a Northumbrian by birth, who settled at Arnesby in 1753, little need be said. He wrote a devotional book, " Helps to Zion's Travellers," since displaced, I fancy, by other guide books to that still puzzling road.

The following anecdote, however, flashes a revealing light across the years:-

Soon after Mr. Hall's settlement at Arnesby he was greatly perplexed with doubts of his call to the work of the ministry and of his qualifications for that all important employ. He desired his wife to go to the deacons and request them to provide a supply for the next Sabbath, as he could not preach. She replied, " Try what the Lord will do for you." On the Saturday he repeated his request. She said, " Stay till the morrow and if they must be told so, go then and tell them yourself." He went, and after telling his dismal tale to the people, an old father in Israel said to him„ " Sir, go up into the pulpit and pray ; and if you find your mind set at liberty, then proceed to preach; if otherwise, come down, and we will spend the time in prayer : for I trust you are with a sympathizing people." He went to prayer and soon found his soul at liberty, so that he preached from those words, "Come, for all things are now ready." The word was greatly blessed almost to all that were present.

Young Robert, a weakling in physical health, was of extra-ordinary mental precocity. He taught himself the alphabet by the aid of the gravestones; it was whispered that he was given to secret prayer even before his speech was plain. He wrote hymns at eight; and at eleven preached to a select company. At fourteen he was baptised - after giving "a very distinct account of his being the subject. of spiritual grace "-and was formally admitted to the Church. His father's congregation subscribed, out of their poverty, to send the boy to Aberdeen University, and at the age of twenty-one he began his ministerial career at Bristol, and soon drew crowded audiences.

Then he went to Cambridge and afterwards to Leicester, where for twenty-four years, to his death in 1831, his eloquence added lustre to the fame of the midland town. Eloquence, indeed! , Either we have not its match now, or else we are less impressionable, for Hall's eloquence drew listeners to their feet and slowly brought them, like sleep-walkers, out, of their pews into the chapel aisles. Olinthus Gregory has pictured the scenes which regularly took place :-

From the commencement of his discourse an almost breathless silence prevailed, deeply impressive and solemnizing from its singular intenseness. Not a sound was heard but that of the preacher's voice - scarcely an eye but was fixed on him - not a countenance that he did not watch, and read and interpret, as he surveyed them again and. again with his rapid, ever excursive glance. As he advanced and increased in animation five or six of the auditors would be seen to rise and lean forward over the front of their pews, still keeping their eyes upon him. Some new or striking senti-ment or expression would, in a few minutes, cause others to rise in like manner; shortly afterwards still more, and soon until, long before the close of the sermon, it often happened that a considerable portion of the congrégation were seen standing - every eye directed to the preacher, yet now and then for a moment glancing from one to another, thus transmitting and reciprocating thought or feeling. Mr. Hall himself, though manifestly absorbed in his subject, was conscious of the whole, receiving new anima-tion from what he thus witnessed, reflecting it back upon those who were already alive to the inspiration, until all that were susceptible of thought and emotion seemed wound up to the utmost limit of elevation on earth, . when he would close and they reluctantly and slowly resume their seats.

I find this all the more astonishing because when I turned to the published works of Robert Hall to judge for myself the eloquence which stirred his contemporaries so deeply, I was grievously disappointed. Even the famous sermon on the death of the Princess Charlotte, which, as was said at the time, would have secured for its author a bishopric, had he belonged to the Established Church, seems cold and dead. But such is often the way with famous orators, whose fame seems inexplicable to a later generation, which misses the fire of delivery, the animated gesture, the flashing eye, the look of inspiration, and the tone of exquisite sympathy or imperious command in the living voice.

Robert Hall's religious opinions interest me little; but the man much. All his life he was martyrised by acute pain, and for twenty years, it is said, he never spent a whole night in bed. He would get up and lie on the floor and smoke and read for hours together. The puzzled doctors could do nothing for him, nor was the secret fully revealed until after death it was found that his "right kidney was entirely filled with a large rough pointed calculus." There lay the cause of his excruciating torment; that was " the body of his death " which he had borne so long. He sought sedatives in tobacco, tea, and opium. As a tea-drinker he outclassed even Dr. Johnson. It was no uncommon thing for him to visit four families in an afternoon and drink seven or eight cups with each.

As a smoker he rivalled his friend, Dr. Parr. " Thank you, Sir! " he once said to a correspondent who had sent him Adam Clark's pamphlet against smoking, " I can't refute his arguments and I can't give up smoking." " I well recollect," wrote Hall's biographer, " entering his apartment just as he had acquired this happy art, and seeing him sit at ease, the smoke rising above his head in lurid spiral volumes, he inhaling and apparently enjoying its fragrance, I could not suppress my astonishment. 'O, Sir,' said he, 'I am only qualifying myself for the Society of a Doctor of Divinity, and this' - holding up the pipe - 'is my test of admission'. His study never lacked an ample store of "kynaster"; he puffed away even on the outside of the mail coaches; and it is naïvely added that "he took nothing whatever with his pipe, but swallowed the saliva as a sort of medicine."

The quantities of laudanum that he took were enormous. In 1812 his dose was from 50 to 100 drops a night; by 1826 it had risen to a thousand ! Naturally, he became a slave to the drug like De Quincey and Coleridge, and it is a tempting speculation whether Robert Hall's eloquence was in any degree attributable to its influence., That is one of the insoluble problems of Coleridge's life; but Hall's reputation for oratory was firmly established long before he sought relief in this direction from physical torture. Moreover, like his mother, who was subject to mental disturbance, Hall had twice to be placed under restraint.

One or two of his best bons mots must be quoted. Of Dr. Watson, Bishop of Llandaff, he said, "He married public virtue in his early days and seemed for ever afterwards to be quarrelling with his wife." And of another parson he said: "He has no grace but divine. He is elegant but cold. It is the beauty of Frost."

So much for Dr. Robert Hall. Travellers used to break their journeys at Leicester in order to hear him preach, or they would time their journeys so as to be there on a Sunday. Of how many pulpit orators of our generation can the same be said? He was once offered £100 by a London bookseller to write a "commendation "- the word now is "appreciation" - for a new preface to Matthew Henry's "Commentaries." Instead of welcoming the opportunity, Hall was seriously upset ! " I write a recommendation to Matthew Henry! " he said. " Never! Mr. ------- must think me a mercenary wretch ! Why did he not offer me £100 to paint a diamond or extol the sweet scent of a violet?"